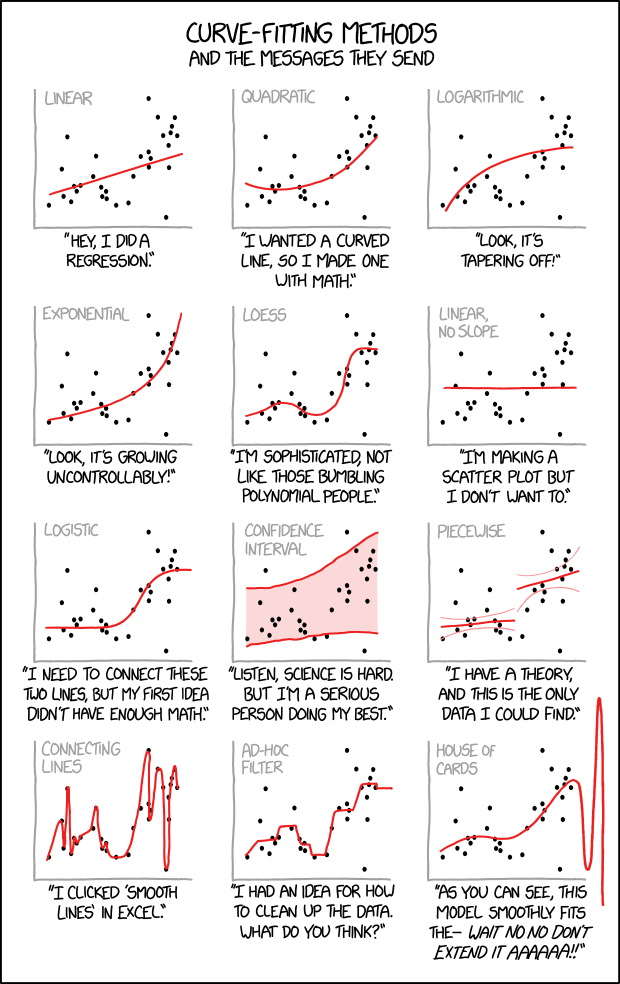

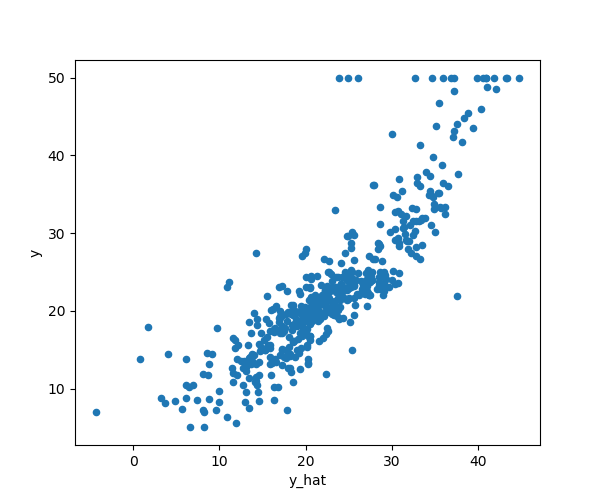

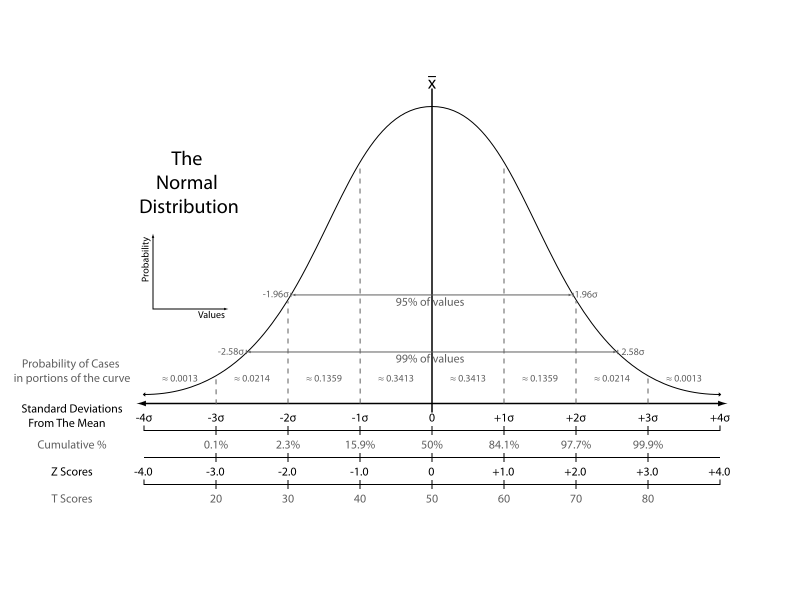

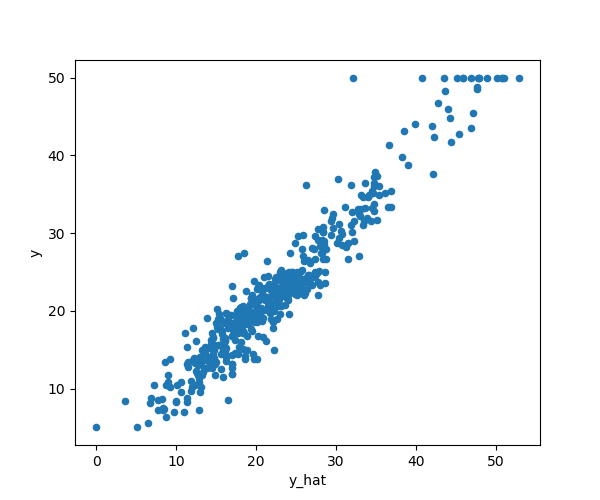

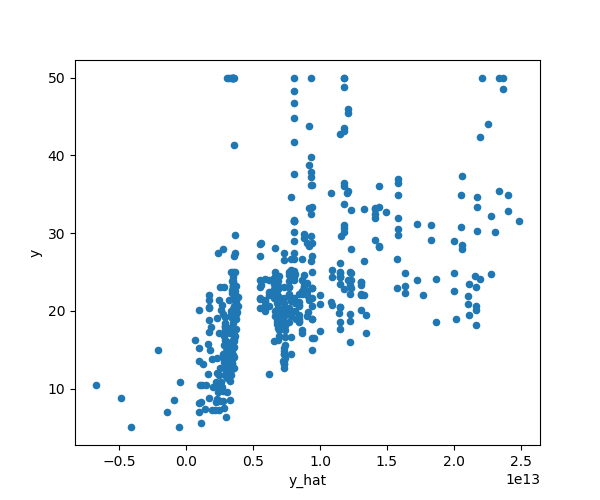

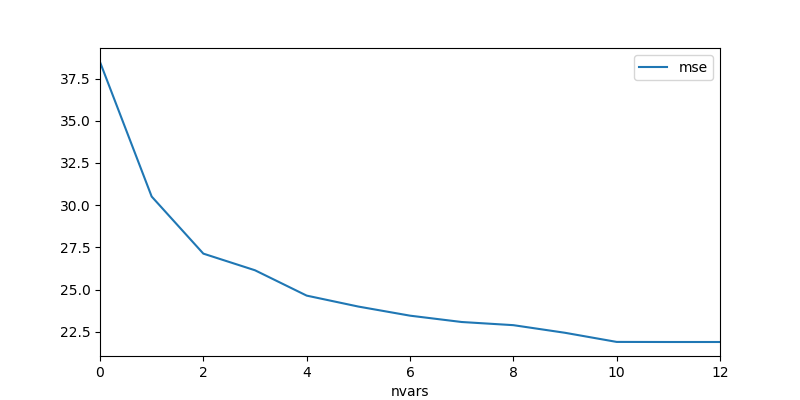

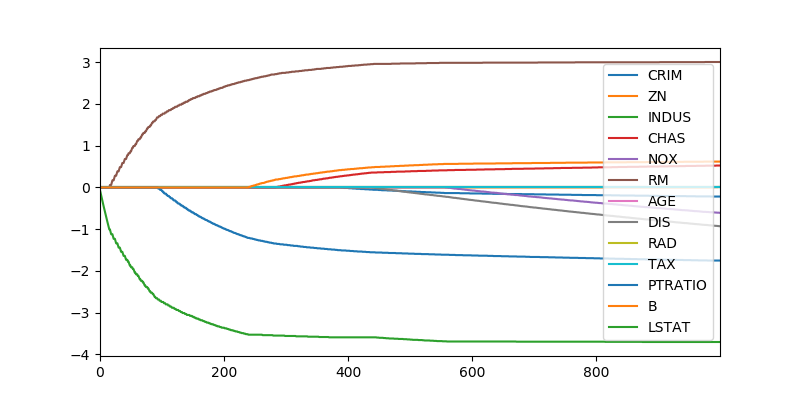

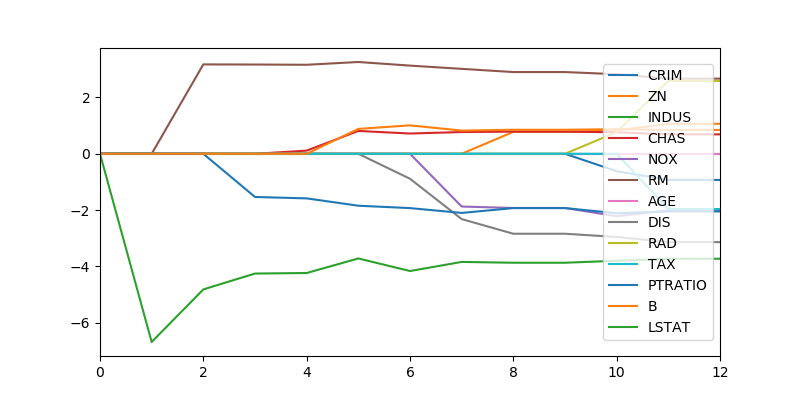

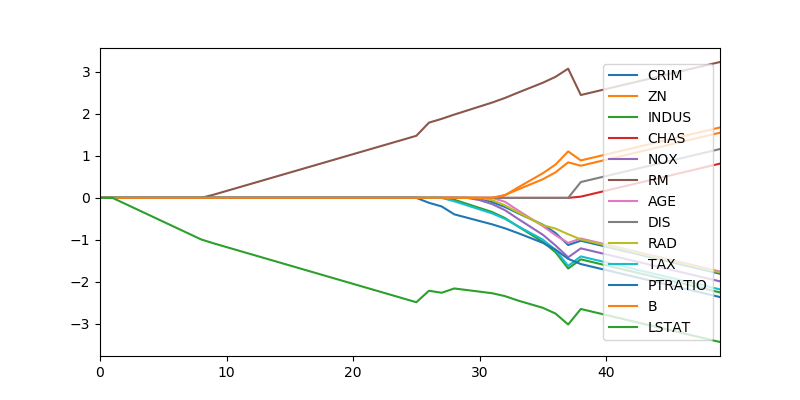

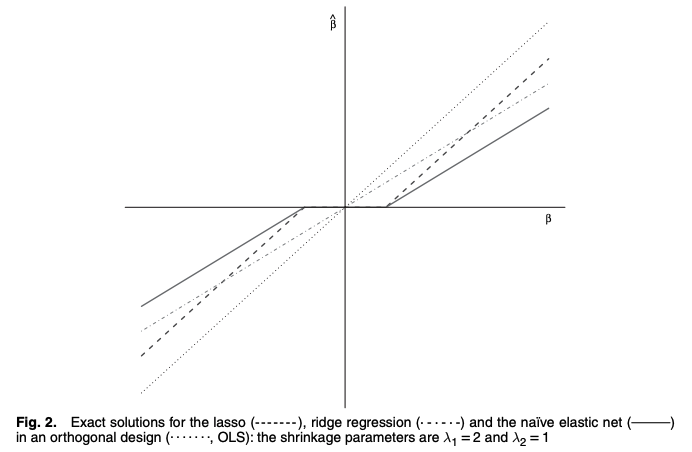

class: center, middle # Linear Models CS534 - Machine Learning Yubin Park, PhD --- class: center, middle Like many problems in science and engineering, we have input `\( \mathbf{X} \)`, output `\( \mathbf{y} \)`, and function `\( f(\cdot) \)`. $$ \mathbf{y} = f(\mathbf{X}) $$ --- class: center, middle However, unlike many other problems, we do not know the function. We need to **reverse-engineer** the function from the pairs of input and output. --- class: center, middle .figure[] .reference[https://xkcd.com/2048/] --- ## Notation Convention A lowercase letter is used for a scalar variable e.g. `\(y\)` A bold, lowercase letter is used for a vector variable e.g. `\(\mathbf{x}\)` A bold, uppercase letter is used for a matrix variable e.g. `\(\mathbf{X}\)` Unless otherwise specified, - `\(y\)` represents a target (or response) variable - `\(\mathbf{x}\)` represents a feature (or input) vector - `\((y, \mathbf{x})\)` represents a pair of a target variable and a feature vector - `\(\mathbf{X}\)` represents a matrix of feature vectors - `\(i\)` and `\(j\)` are used for the row and column indicies, respectively - `\(\mathbf{x}_i\)` represents the `\(i\)`th sample of the feature matrix `\(\mathbf{X}\)` - `\(\mathbf{x}_{(j)}\)` represents the `\(j\)`th column vector of `\(\mathbf{X}\)` - NOTE: `\(\mathbf{X} = [\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2, \cdots, \mathbf{x}_n]^T = [\mathbf{x}_{(1)}; \mathbf{x}_{(2)}; \cdots; \mathbf{x}_{(m)}] \)` A dataset is a collection of samples: `\(\mathcal{D} = [(y_1, \mathbf{x}_1), \cdots, (y_n, \mathbf{x}_n) ]\)` A Greek letter is used for model parameters e.g. `\(\theta, \beta, \alpha, \gamma, \lambda \)` --- ## Loss Function Most of the time, it is impossible to reconstruct the original function - or, there is no way to know the truth. At best, we would want a function that works as "**close**" as possible to the observed data. For that, we need a loss function `\(\mathcal{L}(\cdot,\cdot)\)` that measures how "close" the approximated output (`\(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\)`) and real output (`\(\mathbf{y}\)`) are. $$ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{y}, \hat{\mathbf{y}}) $$ Now, we can write our problem statement in a succint mathematical form: $$ \min_{f} \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{y}, f(\mathbf{X})) $$ We want to find a function that minimizes the loss function. --- class: center, middle Although the problem may seem simple, it is not. The search space of such functions can be **infinitely** huge. However, the problem becomes relatively easier if we constrain the search space. For example, what if the function has a form as follows: $$ y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \cdots + \beta_m x_m $$ --- ## Linear Model With a matrix notation, a [linear model](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linear_model) can be written as follows: $$ \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{X} \mathbf{\beta} $$ This is, perhaps, the most widely used and deeply studied model to this day. This often serves as the baseline model for all other models. Under this class of models, our problem reduces to: $$ \min_{\mathbf{\beta}} \mathcal{L}( \mathbf{y}, \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta}) $$ Our job is to find the coefficients, `\(\mathbf{\beta}\)` --- ## Squared Loss Consider a loss function as follows: $$ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta}) = (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} )^T ( \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} )$$ This is known as a squared loss function. Expanding the matrix notation, we get: $$ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta}) \propto \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \mathbf{x}_i^T \mathbf{\beta})^2}{n} $$ This term is sometimes called as the [Mean Squared Error (MSE)](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mean_squared_error). Note that `\(\epsilon_i=(y_i - \mathbf{x}_i^T \mathbf{\beta})\)` represents an error between the true and approximated functions. We took the mean of squared errors, hence, MSE. --- ## Probabilistic Perspective on MSE Assume that - Each sample is independent - Errors follow a normal distribution, `\(N(0, \sigma^2)\)` $$ \text{likelihood} = \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}\exp{(-\frac{\epsilon_i^2}{2\sigma^2})} $$ $$ \text{log-likelihood} \propto - \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \mathbf{x}_i^T \mathbf{\beta})^2 $$ The squared loss has the same form as the **negative log-likelihood** of the model: $$ \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} + \mathbf{\epsilon} $$ --- ## Least Squares The squared loss function is **differentiable**. It's time for some **calculus**. Differentiating with respect to `\(\mathbf{\beta}\)` gives: $$ -2 \mathbf{X}^T (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta}) = 0 $$ Assuming (for the moment) that `\(\mathbf{X}\)` has full column rank, we have the unique solution: $$ \hat{\mathbf{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{y}$$ NOTE: Minimizing the squared loss function => minimizing the negative log-likelihood => maximizing the likelihood. The least squares solution is also the maximum-likelihood estimator of the model. --- ## Boston House-Price Data (revisited) ```python data = load_boston() X = data.data y = data.target n, m = X.shape # adding the intercept to X X = np.append(np.ones(n).reshape(n, 1), X, axis=1) beta = np.dot(np.linalg.inv(np.dot(X.T, X)), np.dot(X.T, y)) y_hat = np.dot(X, beta) ``` .center[.figure-300[]] --- ## Inference (1) Suppose that our linear model is **true**. Then, our next question is how reliable `\(\hat{\mathbf{\beta}}\)` is? Recall that our samples are perturbed by noise, hence `\(\text{Var}(y)=\sigma^2\)`. $$ \text{Var}(\hat{\mathbf{\beta}}) = \text{Var}((\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{y}) = (\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1} \sigma^2 $$ The coefficients follow a normal distribution, as it is a linear transformation of the normal noise, `\(\mathbf{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^T(\mathbf{y}-\mathbf{\epsilon})\)`. Thus, $$ \hat{\mathbf{\beta}} \sim N(\mathbf{\beta}, (\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1} \sigma^2) $$ The variane, `\(\sigma^2\)`, can be estimated from the samples as follows: $$ \hat{\sigma}^2 = \frac{1}{n-m-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 $$ --- ## Inference (2) A test statistics to see if `\(\beta_j=0\)` (null hypothesis) or not, $$ z_j = \frac{\hat{\beta}_j}{\hat{\sigma}\sqrt{\nu_j}} $$ where `\(\nu_j\)` is the `\(j\)`th diagnoal element of `\((\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}\)`. This value, also known as `\(Z\)`-score, follows a `\(t\)` distribution with `\(n-m-1\)` degrees of freedom. However, with large enough samples, the distribution can be approximated with the standard normal distribution. Note that a large `\(Z\)`-score will reject the null hypothesis. --- class: center, middle .figure[] .reference[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Normal_Distribution.svg] --- ## Boston House-Price Data (again) ```python from collections import Counter sigma = np.sqrt(np.sum(np.square(y - y_hat))/(n-m-1)) XTX = np.linalg.inv(np.dot(X.T, X)) nu = np.diag(XTX) z = beta/sigma/np.sqrt(nu) z_counter = Counter({k:np.abs(v) for k, v in zip(columns, z)}) for k, v in z_counter.most_common(): print("{0:<12}{1:>5.2f}".format(k, v)) ``` ```bash LSTAT 10.35 RM 9.12 DIS 7.40 PTRATIO 7.28 Intercept 7.14 NOX 4.65 RAD 4.61 B 3.47 ... ``` Are these important variables that affect the median house prices? --- ## Expanding Features Linear models can capture the **linear** relationship between the **features** and target. So far, we assumed the features are the same as the raw data. However, the features can be **engineered** and **expanded** in various ways: - Non-linear transformation, for example, `\( \log(x_j)\)` - Basis expansion, such as `\(x_j^2\)`, `\(x_j^3\)` - Interaction variables, such as `\(x_j x_k\)` - Dummy coding of categorical variables - Thresholding, for example, `\( I(x_j > 0) \)` In other words, linear models can capture the linear relationship the **engineered** features and target. Note that such relationships may have been non-linear in the original feature space. --- ## Poly Features for Boston House-Price Data (1) ```python from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures poly = PolynomialFeatures(2, interaction_only=True) X = poly.fit_transform(data.data) n, m = X.shape y = data.target beta = np.dot(np.linalg.inv(np.dot(X.T, X) ), np.dot(X.T, y)) y_hat = np.dot(X, beta) ``` .center[.figure-300[]] --- ## Poly Features for Boston House-Price Data (2) Let's be more ambitious. We will include the 2nd-degree terms too e.g. `\(x_j^2\)`. ```python poly = PolynomialFeatures(2, interaction_only=False) ``` .center[.figure-300[]] .center[Oops, what's going on?] --- ## Key Assumption of Linear Models When deriving the least squares solution, we assumed as follows: > "Assuming (for the moment) that `\(\mathbf{X}\)` has full column rank, ..." What if the assumption does not hold? ```python XTX = np.linalg.inv(np.dot(X.T, X)) nu = np.diag(XTX) print(nu) ``` ```bash [ 2.09964081e+03 6.48910460e+00 9.82364219e-03 1.06748344e+00 5.55553419e+27 1.58789227e+03 1.00485565e+01 8.93892342e-03 4.60058666e+00 9.53811061e-01 3.03175549e-03 3.59185617e-01 9.61443244e-04 1.22190745e-01 1.90169867e-07 6.20707879e-03 3.30371457e-02 4.12300648e-02 1.15150963e-01 5.30005074e-04 1.78782515e-06 1.42266526e-03 5.73088861e-02 2.87256702e-04 ... ``` Notice that `\(\nu_5=5.55553419e27\)`; extremely large value. --- class: center, middle ## Conundrum for Linear Models .pure-table.pure-table-bordered.pure-table-striped.smaller-font[ | | Basic Features (or low-dimensional data) | Expanded Features (or high-dimensional data) | | ---- | --------------- | ------------------- | | Strength | Simple and numerically stable | Increased predictive power | | Weakness | Predictive power is limited | Numerically unstable, can violate the key assumption. Prone to [overfitting](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overfitting) the data. | ] Are there ways to have the best of both? An approach that produces a stable model with a large number of features? --- class: middle In fact, there are some nice alternatives. - Subset Selection Methods - Forward Stepwise Regression - Forward Stagewise Regression - Least Angle Regression - Shrinkage Methods - Ridge Regression - Lasso - Elastic-Net Regression Note that there are many other methods. These are just the topics covered in this class. --- class: center, middle .figure-300[] .reference[https://xkcd.com/287/] --- ## Forward Stepwise Regression (1) Staring with the intercept, we will sequentially add one variable at a time that most improves the fit. ```python col_sel = ["Intercept"] columns.remove("Intercept") while len(columns) > 0: col = columns[0] mse_min = np.inf for col in columns: X_tmp = X_df.loc[:,col_sel + [col]] XTXinv = np.linalg.inv(np.dot(X_tmp.T, X_tmp)) beta = np.dot(XTXinv, np.dot(X_tmp.T, y)) y_hat = np.dot(X_tmp, beta) mse = np.mean(np.square(y - y_hat)) if mse < mse_min: mse_min = mse col_best = col columns.remove(col_best) col_sel.append(col_best) print(col_sel) ``` ```bash ['Intercept', 'LSTAT', 'RM', 'PTRATIO', 'DIS', 'NOX', 'CHAS', 'B', 'ZN', 'CRIM', 'RAD', 'TAX', 'INDUS', 'AGE'] ``` --- ## Forward Stepwise Regression (2) A greedy approach for selecting the best subset of variables. Although it produces a suboptimal solution, a couple of advantages: - Computationally fast - Statistically stable: This approach produces a **high-bias low variance** solution. We will revisit this subject in the bias-variance section. MSE reduces as more variables are added as follows: .center[.figure-250[]] --- ## Forward Stagewise Regression (1) Re: Forward "Stepwise" Regression, - What if there is no clear winner in improving the fit? - A variable may be picked simply due to the sampling properties - Fully adding a variable at each iteration may seem less prudent given the greedy nature of the approach **Forward "Stagewise" Regression** remedies these concerns by taking a smaller step of adding a variable: 1. Start with the intercept, `\(\hat{\mathbf{\beta}} = [0, 0, ..., 0]^T\)` 2. Calculate the residuals, `\(\mathbf{r} = \mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}\)` 3. Find the variable, `\(\mathbf{x}_{(j)}\)`, that is most correlated with the residuals 4. Calculate the simple linear regression coefficient of the residuals, `\(\gamma_j\)` for the selected variable 5. Update `\(\hat{\beta}_j = \hat{\beta}_j + \delta \gamma_j \)`, where `\(0 < \delta < 1\)` 6. Repeat from Step 2 till non of the variables have correlation with the residuals --- ## Forward Stagewise Regression (2) ```python X = scale(data.data) # NOTE: Standardize X to have zero mean and unit variance y = y - np.mean(y) nsteps = 1000 delta = 1e-2 beta = np.zeros(m) for s in range(nsteps): r = y - np.dot(X, beta) mse_min, j_best, gamma_best = np.inf, 0, 0 for j in range(m): gamma_j = np.dot(X[:,j], r)/np.dot(X[:,j], X[:,j]) mse = np.mean(np.square(r - gamma_j * X[:,j])) if mse < mse_min: mse_min, j_best, gamma_best = mse, j, gamma_j if np.abs(gamma_best) > 0: beta[j_best] += gamma_best * delta ``` `\(\delta\)` becomes the hyperparameter of the model. As can be seen, a lot more iterations needed than Forward Stepwise Regression. --- ## Forward Stagewise Regression (3) .center[.figure-300[]] .center[Coefficients converge after 1,000+ iterations. With a smaller `\(\delta\)`, it takes longer to converge.] --- ## Least Angle Regression (1) Re: Forward Stagewise Regression, - Too many iterations for the coefficients to converge - Perhaps, due to the "tiny" step at each iteration Least Angle Regression (LAR) is an efficient alternative to Forward Stagewise Regression by taking a **"calculated bigger"** step at each iteration. Also, LAR can be viewed as [a kind of "democratic" version of Forward Stepwise Regression](http://statweb.stanford.edu/~tibs/ftp/lars.pdf). LAR is closely connected to other important algorithms in machine learning, such as [Lasso](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lasso_(statistics)) and [Boosting](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boosting_(machine_learning)). For more information, please see: https://web.stanford.edu/~hastie/TALKS/larstalk.pdf --- ## Least Angle Regression (2) The first few steps of the algorithm: 1. Initiallize `\(\mathbf{r} = \mathbf{y} - \bar{\mathbf{y}}\)` 1. Find the variable `\(\mathbf{x}_{(j)}\)` most correlated with `\(\mathbf{r}\)` 1. Move `\(\beta_j\)` from 0 towards its least-squares coefficient `\(\langle\mathbf{x}_{(j)},\mathbf{r}\rangle\)`, until some other competitor `\(\mathbf{x}_{(k)}\)` has as much correlation with the current residual as does `\(\mathbf{x}_{(j)}\)` 1. Re-calcaulte the residuals 1. Move `\(\beta_j\)` and `\(\beta_k\)` in the direction defined by their joint least squares coefficient of the current residual on `\((\mathbf{x}_{(j)}, \mathbf{x}_{(k)})\)`, until some other competitor `\(\mathbf{x}_{(l)}\)` has as much correlation with the current residual. 1. Continue in this way until all variables are activated. The key is that we can derive **"the exact size"** of the step to take until the other variable shows up. --- ## Least Angle Regression (3) ```python beta_lst = [np.dot(X[:,j], y)/np.dot(X[:,j], X[:,j]) for j in range(m)] mse_lst = [np.sum(np.square(y - np.dot(X[:,j], beta_lst[j]))) for j in range(m)] j_init = np.argmin(mse_lst) var_inactive = np.full(m, True) var_inactive[j_init] = False while np.any(var_inactive): var_active = ~var_inactive r = y - np.dot(X, beta) beta_k = beta[var_active] X_act = X[:,var_active] gamma = np.dot(np.linalg.inv(np.dot(X_act.T, X_act)), np.dot(X_act.T, r)) Xgm = np.dot(X_act, gamma) alpha_min, j_best = np.inf, -1 for j in np.where(var_inactive)[0]: alpha_a = np.dot(Xgm - X[:,j], r)/np.dot(Xgm - X[:,j], Xgm) alpha_b = np.dot(Xgm + X[:,j], r)/np.dot(Xgm + X[:,j], Xgm) alpha = min(np.clip(alpha_a, 0, 1), np.clip(alpha_b, 0, 1)) if alpha < alpha_min: alpha_min, j_best = alpha, j alpha_min = np.clip(alpha, 0, 1) beta[var_active] += (alpha_min * gamma) var_inactive[j_best] = False ``` --- ## Least Angle Regression (4) .center[.figure-300[]] .center[Took 12 iterations to finish. Similar results with Forward Stagewise Regression.] --- ## Shrinkage Methods Due to the sampling properties of the data, the coefficients are either **over-** or **under-estimated**. Shrinkage methods bias the coefficients to be **under-estimated** in exchange for the stability (i.e. low variability). In contrast to the subset methods, > "By retaining a subset of the predictors and discarding the rest, subset selection produces a model that is interpretable and has possibly lower prediction error than the full model. However, because it is a **discrete process** — variables are either retained or discarded — it often exhibits **high variance**, and so doesn’t reduce the **prediction error** of the full model. Shrinkage methods are more **continuous**, and don’t suffer as much from high variability." - from [Chapter 3.4 of ESL](https://web.stanford.edu/~hastie/ElemStatLearn/) --- ## Ridge Regression The loss function of Ridge Regression is as follows: $$ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta}) = (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} )^T ( \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} ) + \lambda \mathbf{\beta}^T\mathbf{\beta}$$ Note the additional term, `\(\mathbf{\beta}^T\mathbf{\beta}\)`, also known as a penalty term. This term **penalizes** the loss function for a large `\(\mathbf{\beta}\)`. A closed-form solution: $$ \hat{\mathbf{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X} + \lambda \mathbf{I})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{y}$$ Even if `\(\mathbf{X}\)` is not of full rank, a unique solution exists. --- ## Lasso (1) The loss function of Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) is as follows: $$ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta}) = (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} )^T ( \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} ) + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^m |\beta_j| $$ Note the penalty term is the sum of absolute values. No closed-form solution, as the penalty term is non-linear. However, many efficient solutions exist: [subgradient methods](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subgradient_method), [LARS](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Least-angle_regression), [proximal gradient methods](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proximal_gradient_method) --- ## Lasso (2) Proximal Graident Version: ```python def soft_thr(beta, lmbd): beta[np.abs(beta) <= lmbd] = 0 beta[beta > lmbd] -= lmbd beta[beta < -lmbd] += lmbd return beta def loss_func(y, X, beta, lmbd): return (np.sum(np.square(y - np.dot(X, beta))) + lmbd * np.sum(np.abs(beta))) lr, max_iter, i = 1e-3, 100, 0 beta, loss = np.zeros(m), np.inf beta_new = soft_thr(lr * np.dot(X.T, y), lmbd) loss_new = loss_func(y, X, beta, lmbd) while loss_new < loss and i < max_iter: loss, beta = loss_new, beta_new r = y - np.dot(X, beta) beta_new = soft_thr(beta + lr * np.dot(X.T, r), lmbd) loss_new = loss_func(y, X, beta_new, lmbd) i += 1 ``` --- ## Lasso (3) .center[.figure-300[]] .center[Moving `\(\lambda\)` from 3.5 to 0 in a linear scale. Compare with LAR and Forward Stage Regression.] --- ## Elastic-Net Regression (1) The loss function of Elastic-Net is as follows: $$ (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} )^T ( \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{\beta} ) + \lambda(\alpha \mathbf{\beta}^T \mathbf{\beta} + (1-\alpha) \sum_{j=1}^m |\beta_j|) $$ A linear combination of the Ridge and Lasso penalty terms. Minimizing this loss function is equivalent to a lasso-type optimization problem. For more information, please read [the original paper](https://web.stanford.edu/~hastie/Papers/B67.2%20%282005%29%20301-320%20Zou%20&%20Hastie.pdf) and [slides](https://web.stanford.edu/~hastie/TALKS/enet_talk.pdf). --- ## Elastic-Net Regression (2) .center[.figure-300[]] .center[.reference[[H. Zou and T.Hastic. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Statistit. Soc. B](https://web.stanford.edu/~hastie/Papers/B67.2%20%282005%29%20301-320%20Zou%20&%20Hastie.pdf)]] --- class: center, middle ## Questions?